"The Communists disdain to conceal their views and aims. They openly declare that their ends can be attained only by the forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions. Let the ruling classes tremble at a Communistic revolution. The proletarians have nothing to lose but their chains. They have a world to win.” Marx and Engels, Manifesto of the Communist Party.

Lenin or Kautsky?

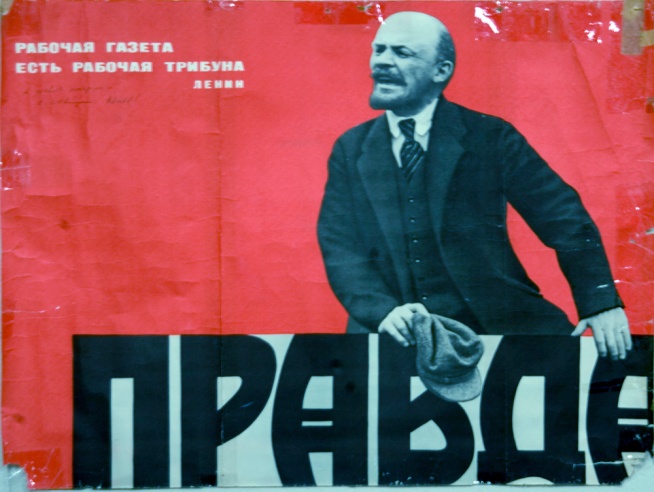

Today we are facing a massive retreat from Leninism on the left. Under attack from the global crisis the working class and the oppressed are moving to the left in opposing its effects - austerity, ‘precarity’, mass unemployment and political repression - and launching Arab Springs, riots, occupations and armed struggles against bourgeois dictators. The masses are hungry for ideas on how to challenge and overcome capitalism. Yet there is no revolutionary mass party to turn to. The ostensible revolutionary left moves to offer this leadership.

However this left is afraid to be identified with what is perceived as a failure of 20th century socialism and communism. It runs a mile from the ‘Dictatorship of the Proletariat’. To appease the radicalised masses most of the left is re-inventing its Marxism along the lines of the Chavista 21st century socialism, or the broad Marxist party of the 2nd International ‘democratic socialism’ associated with Karl Kautsky. It either renounces Bolshevism as an historic dead-end, or attempts to make the Bolsheviks and Lenin in particular, no more than Russian Kautskys. Trotsky is also a target because he renounced his conciliation with the Mensheviks and Kautsky to join Lenin and the Bolsheviks in 1917. Trotsky stands or falls with Lenin.

As we will see with bourgeois professors professing Marxism, the WSJ Roubini interview, TIME magazine cover story ‘Rethinking Marx’ , Hugo Chavez painted as ‘Marxist’ with links to Cuba and China, the left has no credibility unless its stakes a claim to the Marx franchise. So is this Marx with or without Lenin? That is the question. How do we know? Who was the real Lenin? Was he the heir of Marx and a proponent of fusing theory and practice, or was he a renegade from ‘authentic’ Marxism rather than the ‘renegade Kautsky’? Was the Marxist party a vanguard party in Marx’s sense of not being ‘separated from the working class’? Was the ‘democratic centralism’ Lenin practiced democratic or was it a precursor to Stalin’s dictatorship. Was Lenin responsible for the degeneration of today’s political sects and their isolation from the masses? It sounds confusing but it’s not really. We don’t have to ‘rediscover’ or ‘reload’ Lenin, his history is written by the Bolshevik Revolution.

Without the Bolsheviks and their undisputed leader Lenin, there would have been no Russian revolution so the left as we know it today would not exist. The history of the 20th century would be very different. Marxism would not have been kept alive in the 20th century and remain a powerful class ideology today. There would be no Marx revival, symbolic or real. But because the Bolsheviks and Lenin did exist they and he will continue to inspire the masses today in the belief that socialist revolution is not only possible but necessary. If we do not defeat the all out attack on Lenin and Bolshevism, reactionaries ranging from centrists who claim to be Marxists (the new batch of Mensheviks) to reformists and anarchists, in the name of ‘democracy’, horizontalism, of ‘not taking power’, and so on, will lead new layers or revolutionaries back into the swamp of reformism, reaction and climate catastrophe. Against all anti-Leninists our task is to Reboot Lenin. This means restoring Lenin as the leading champion of Marx (and Engels) in the 20th century.

For Marx Program came first

“The Communists are distinguished from the other working-class parties by this only: 1. In the national struggles of the proletarians of the different countries, they point out and bring to the front the common interests of the entire proletariat, independently of all nationality. 2. In the various stages of development which the struggle of the working class against the bourgeoisie has to pass through, they always and everywhere represent the interests of the movement as a whole.” Manifesto of the Communist Party

The Communist Manifesto competed in the workers movement of its time with the rival programs of the Bakuninists, Proudhonists and the Blanquists. For Marx the program was a fusion of scientific theory and socialist practice. Marx’s critique of capitalism revealed its laws of development and provided a programmatic guide to the development of the proletariat as the revolutionary class. Marx was almost alone as the drafter of Communist program and of developing that program on the basis of class struggle. In his 18th Brumaire of Louise Bonaparte written 4 years after the Manifesto, Marx revealed the class interests of the bourgeoisie which despite its factions united to maintain its class rule by concentrating state power in the figure of a Bonapartist dictator. But as the Bonaparte personified state power as ‘above classes’, he also represented its fallibility, as the state became ripe for ‘smashing’ and replacement by a proletarian state –the “Dictatorship of the Proletariat”.

This development of the Marxist program was based on Marx’s observations derived from his theory of the class nature of the state as the state of the ruling class. But as a guide to revolutionary practice it had to be tested in the class struggle with the active collaboration of the members of the party. Unless the Marxist program won the support of a majority of politically active workers there could be no revolution. Its first major test came with the Paris Commune of 1871.

Marx wrote later in a Letter to Krugelmann during the days of the Paris Commune:

"If you look at the last chapter of my Eighteenth Brumaire you will find that I say that the next attempt of the French revolution will be no longer, as before, to transfer the bureaucratic-military machine from one hand to another, but to smash it, and this is essential for every real people's revolution on the Continent. And this is what our heroic Party comrades in Paris are attempting. What elasticity, what historical initiative, what a capacity for sacrifice in these Parisians! After six months of hunger and ruin, caused rather by internal treachery than by the external enemy, they rise, beneath Prussian bayonets, as if there had never been a war between France and Germany and the enemy were not at the gates of Paris. History has no like example of a like greatness." [Our emphasis]

Marx had written 20 years earlier at the conclusion of the 18th Brumaire “...when the imperial mantle finally falls on the shoulders of Louis Bonaparte, the bronze statue Napoleon will crash from the top of the Vendome Column”. This was now put into practice by the Communards as they took steps to ‘smash the state’.

As Engels puts it:

"From the outset the Commune was compelled to recognize that the working class, once come to power, could not manage with the old state machine; that in order not to lose again its only just conquered supremacy, this working class must, on the one hand, do away with all the old repressive machinery previously used against it itself, and, on the other, safeguard itself against its own deputies and officials, by declaring them all, without exception, subject to recall at any moment."

Engels describes this process as the “shattering of former state power and its replacement by a new really democratic state”. (Engels, Introduction to The Civil War in France.)

The Commune was a watershed that tested the Marxist program in the throes of civil war and proved that the smashing of the state and its replacement by a workers state was necessary to complete the proletarian revolution, and to defend it from the bourgeois counter-revolution. The failure to smash the state would inevitably mean defeat. The program proved its superiority in practice over the Proudhonists, Blanquists, and the Anarchists in front of the world working class. All had a program that would lead to defeat. The Proudhonists had no conception of organising the proletariat as a class to smash the state and take power. The Blanquists organised as a conspiratorial elite separate from the proletariat. The Anarchists thought that capitalist exploitation derived from its state power and once the state was smashed the proletariat did not need a state to defend its class rule. (Engels, Introduction to The Civil War in France)

Marx found two weaknesses in the Commune in its failure to implement the Dictatorship of the Proletariat fully. Despite forming a popular militia, it failed to march on Versailles to take advantage of the enemy retreat. “They did not want to start a civil war, as if that mischievous abortion Thiers had not already started a civil war with his attempt to disarm Paris!” .“The Central Committee surrendered its power” to the Commune too soon. [Letter to Krugelman].

In The Civil War in France Marx explains that the Central Committee (made up of a Blanquist majority and Proudhonist minority) was not prepared for an insurrection and tried to compromise with the bourgeois regime. It lacked a firm Marxist leadership and did not understand the necessity to take power. That is why it failed to march on Versailles.

Lenin writing on the Commune comes to the same conclusion – the absence of a Marxist party in the leadership meant the reformists prevailed:

"But two mistakes destroyed the fruits of the splendid victory. The proletariat stopped half-way: instead of setting about “expropriating the expropriators”, it allowed itself to be led astray by dreams of establishing a higher justice in the country united by a common national task; such institutions as the banks, for example, were not taken over, and Proudhonist theories about a “just exchange”, etc., still prevailed among the socialists. The second mistake was excessive magnanimity on the part of the proletariat: instead of destroying its enemies it sought to exert moral influence on them; it underestimated the significance of direct military operations in civil war, and instead of launching a resolute offensive against Versailles that would have crowned its victory in Paris, it tarried and gave the Versailles government time to gather the dark forces and prepare for the blood-soaked week of May." [Our emphasis]

Even in defeat the Commune proved the fundamental correctness of the Marxist program; only the working class organised by a Marxist vanguard was capable of smashing the state and introducing the Dictatorship of the Proletariat (the “really new democratic state”).

20 years later in his Introduction to The Civil War in France, referring to the ‘opportunism’ trend in the 2nd International, Engels concluded:

"Of late, the Social Democratic philistine has once more been filled with wholesome terror at the words: Dictatorship of the Proletariat. Well and good gentlemen, do you want to know what this dictatorship looks like? Look at the Paris Commune. That was the Dictatorship of the Proletariat." [Our emphasis]

Though the Marxist program was proven correct in by the Commune, the International Workingmen’s Association (the ‘First International’) did not survive long. In the ebb in the class struggle that followed, two Marxist tendencies emerged both drawing on the Paris Commune, one to advance to revolution and the other to retreat to reformism. In the Second International the revolutionary wing came to be associated with Lenin, Trotsky and Luxemburg. The reformist wing was associated with Bernstein and Kautsky. Both trace their Marxist credentials back to the Commune and the revised Communist Manifesto. (Karl Korsch, Introduction to the Critique of the Gotha Program)

Lenin and Trotsky: Kautsky and the Paris Commune

It is no accident that both Lenin and Trotsky went back to the Paris Commune and Marx and Engels for guidance during and after the Bolshevik seizure of power. Lenin did so to get to the roots of the Kautsky’s ‘centrism’ and betrayal of revolution in Russia and Germany. Trotsky did so during the height of the civil war in response to Kautsky’s attack on the ‘Red Terror’. They both traced the ultimate split in the Marxist movement over the question of the proletariat’s ‘authority’ to impose a Dictatorship of the Proletariat back to the Paris Commune.

Engels writing in the immediate aftermath of the Commune’s defeat in 1873 put his finger on the fear that held back the proto-Mensheviks from the military seizure of power:

"Have these gentlemen ever seen a revolution? A revolution is certainly the most authoritarian thing there is; it is an act whereby one part of the population imposes its will upon the other part of the population by means of rifles, bayonets and cannon, all of which are highly authoritarian means. And the victorious party must maintain its rule by means of the terror which it arms inspire in the reactionaries. Would the Paris Commune have lasted more than a day if it had not used the authority of the armed people against the bourgeoisie? Cannot we, on the contrary, blame it for having made too little use of that authority?" [On Authority]

Both Lenin and Trotsky follow Marx and Engels’ view that the leaders of the Communards made “too little use of that authority” and “stopped halfway” (Lenin’s phrase) because they lacked a Marxist leadership and were still influenced by petty bourgeois socialism (Proudhon’s reforms, Blanqui’s adventurism) and Bakunin’s petty bourgeois hostility to the proletarian dictatorship. They shared the view that conditions were not ripe for revolution, but that once the armed workers were forced to defend Paris from the Prussian and French armies, it was necessary to pursue the civil war to the end. They agreed with Marx and Engels that the failure to do this was due to the absence of Marxist majority in the Central Committee of the National Guard.

In drafting The State and Revolution, Lenin traces Kautsky’s break from the Marxist program back to the Commune. While Marx and Engels amended the Manifesto to incorporate the “smashing of the state” and the “Dictatorship of the Proletariat”, Kautsky is opposed the “destruction of state power” and instead speaks of “shifting the balance of forces within state power”.

Lenin exclaims:

"This is a complete wreck of Marxism!! All the lessons and teachings of Marx and Engels of 1852-1891 are forgotten and distorted. “The military-bureaucratic state machine must be smashed”, Marx and Engels taught. Not a word about this. The philistine utopia of reform struggle is substituted for the dictatorship of the proletariat." [Lenin, Marxism on the State: preparatory Material for the book The State and Revolution. 78 [Not online]

Lenin goes on to point out that the old bourgeois state has to be replaced by a new proletarian state so that the proletariat as a class can “suppress the bourgeoisie and crush their resistance.” While the Commune immediately took on the form of a proletarian state by replacing the standing army with armed workers, it could not complete its task of workers democracy (in which all officials were elective, responsible and revocable) because it failed to crush the resistance of the bourgeoisie. The Central Committee feared imposing the ‘terror’ of their class authority on the class enemy. It sought ‘compromise’ instead. As Trotsky found in Kautsky’s writings on the Commune, he agreed with the Central Committee!

Trotsky, onboard his military train in 1921 replying to Kautsky’s attack on Red Terror [the Red Army putting down counter-revolution ruthlessly], found Kautsky’s fear of the ‘authority’ of the proletarian dictatorship in Russia during the Civil War was already rooted in his fear of the ‘Red terror’ of the Civil War in France. Kautsky could easily agree with Marx that in 1871 the revolution was premature because the conditions were not ripe and the workers unprepared. Yet when facing an actual civil war, instead of following Marx and Engels into battle to defeat the non-Marxist leadership and impose a strong central military command, Kautsky would have sided with the ‘compromisers’ who hoped to do a deal with Thiers by holding an election to make the Commune ‘legal’!

As Trotsky argues, Kautsky put the ‘democracy’ of the Commune ahead of the Central Committee’s military campaign to defeat the National Assembly:

"In supporting the democracy of the Commune, and at the same time accusing it of an insufficiently decisive note in its attitude to Versailles, Kautsky does not understand that the Communal elections, carried out with the ambiguous help of the “lawful” mayors and deputies, reflected the hope of a peaceful agreement with Versailles. This is the whole point. The leaders were anxious for a compromise, not for a struggle. The masses had not yet outlived their illusions."

Nor had Kautsky , whose pacifist confusion would have done nothing to help smash those illusions. Trotsky ‘gets’ Kautsky:

"When one considered the execution of counter-revolutionary generals as an indelible “crime”, one could not develop energy in pursuing troops who were under the direction of counter-revolutionary generals." [The Paris Commune and Soviet Russia],

In other words Kautsky was already a ‘centrist’. He quoted Marx in theory but then drew reformist practical conclusions. He put bourgeois democracy ahead of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat, because the “workers were not prepared”. His centrism was to go unchallenged for decades by Engels and others in the 2nd International though Engels selected Bebel in his place as literary executor of Marx and Engels after the latter’s death.

The Gotha Program abandons Marxist program

Four years after the defeat of the heroic C0mmunards which put the Marxist program to its first test in a revolutionary situation, Marx was forced to come to the defence of the Communist Manifesto in his Critique of the Gotha program in 1875. Having dispensed with the Proudhonists who rapidly declined, and split with Bakunin in 1873, Marx was now facing a split with the German ‘Marxists’ the Eisenarchers, who at the unity congress with the Lassalleans turn out to be more followers of Lassalle than Marx. Marx argued that the resulting United Workers Party of Germany abandoned the “Communist” program for that of Lassalle which ignored social relations, surplus-value, internationalism, and the class nature of the state, and “returned” to a reformist view of the German state redistributing ‘aid’ to workers on the basis of ‘equal right’. It was an “extremely disorganized, confused, fragmented, illogical and disreputable Programme”, and had it been perceived as such by the enemies of the proletariat, Marx and Engels stated they would have been forced to dissociate themselves from it. (cited in Korsch, Introduction to the Critique of the Gotha Program)

Marx writes in the Critique:

"Since Lassalle's death, there has asserted itself in our party the scientific understanding that wages are not what they appear to be -- namely, the value, or price, of labor—but only a masked form for the value, or price, of labor power... And after this understanding has gained more and more ground in our party, some return to Lassalle's dogma although they must have known that Lassalle did not know what wages were, but, following in the wake of the bourgeois economists, took the appearance for the essence of the matter." [Our emphasis]

Marx reveals here that against his own dialectic science, Lassalle’s theory is pre-Marxist ideology going back to Malthus and Ricardo. Wages are the price of labor (not labor power) so the basis of exploitation is the underpaying of the exchange value of labor. This is the ‘appearance’ since the ‘essence’ of capitalist social relations of production ‘appear’ (are inverted) as relations of exchange. If exploitation occurs by paying labor less than its value, then it can be rectified by ‘equalising exchange’ through state aid. However, Marx had already proven scientifically that this cannot be the case in Capital, and more popularly in Wages, Prices and Profits. Exploitation occurs when the commodity labor power is bought at its value, and yet because it is the only commodity with a use value that can produce more than its own value, the capitalist appropriates a ‘surplus-value’. Hence the state cannot become the basis of reforms that guarantee the “undiminished proceeds of labour” by means of a “fair distribution” of income based on an ideal of “equal right”. It is necessary to overthrow the state and expropriate the expropriators!

Thus, Marx makes clear that the Gotha Program is a retreat from his Marxism to the petty bourgeois reformist utopia of a ‘vulgar socialism’:

"Any distribution whatever of the means of consumption is only a consequence of the distribution of the conditions of production themselves. The latter distribution, however, is a feature of the mode of production itself. The capitalist mode of production, for example, rests on the fact that the material conditions of production are in the hands of non-workers in the form of property in capital and land, while the masses are only owners of the personal condition of production, of labor power. If the elements of production are so distributed, then the present-day distribution of the means of consumption results automatically. If the material conditions of production are the co-operative property of the workers themselves, then there likewise results a distribution of the means of consumption different from the present one. Vulgar socialism (and from it in turn a section of the democrats) has taken over from the bourgeois economists the consideration and treatment of distribution as independent of the mode of production and hence the presentation of socialism as turning principally on distribution. After the real relation has long been made clear, why retrogress again?" [Our emphasis]

Lenin recognised that Marx’ Critique was a powerful analysis that developed the program of the Communist Manifesto on the transition from capitalism to communism. Not only did he critique Lassalleanism as a vulgar socialism tied to the German capitalist state, he showed how the capitalist state must be overthrown and give way to a period of transition to socialism (the Dictatorship of the Proletariat) that creates the conditions for communism and the withering away of the state.

“The whole theory of Marx is the application of the theory of development – in its most consistent, complete, considered and pithy form – to modern capitalism. Naturally, Marx was faced with the problem of applying this theory both to the forthcoming collapse of capitalism and to the future development of future communism...it is possible to determine more precisely how democracy changes in the transition...” (The State and Revolution Chapter 5)

Thus Marx in his Critique, destroys all possibility of a peaceful transition from bourgeois to proletarian democracy at the very time when German Social Democracy is opportunistically vulgarising Marxism into a reformist utopian program. First, Marx shows how bourgeois democracy is a formality for the big majority (the working class) because bourgeois democracy can only be a bourgeois dictatorship of the minority over the majority. Second, to bring about proletarian democracy the Dictatorship of the Proletariat is necessary to smash the bourgeois dictatorship.

“Only in communist society, when the resistance of the capitalists has been completely crushed, when the capitalists have disappeared, when there are no classes (i.e. when there is no distinction between the members of society as regards their relations to the social means of production), only then “the state...ceases to exist” and “it becomes possible to speak of freedom”. Only then will a truly complete democracy become possible and be realised...Only then will democracy begin to wither away.” (ibid)

Korsch spells the wider reasons why Marx and Engels took their critique so seriously:

“In the middle of the 1870s, then, Marx and Engels thought it was far more possible than they had ten years earlier for the socialist and communist movement in the advanced countries to return to the ‘old audacity’ of the 1847-8 Manifesto by exhibiting a ‘declaration of principles’. In any case, they thought that the movement had developed to an extent that any retreat from what was said in 1864 must appear to be an unforgivable crime against the future of the workers’ movement. Thus Marx himself says in the note accompanying his Critique of the Gotha Programme:there was no need to make a ‘declaration of principles’ when conditions did not allow it, but when conditions had progressed so much since 1864, it was utterly impermissible to ‘demoralize’ the party with a shallow and unprincipled programme.

This illustrates some of Marx’s preoccupations when writing the Critique of the Gotha Programme. He demanded from the ‘Declaration of Principles’ of the most advanced Socialist Democratic party as a minimum the same level of principle and concrete demands as he himself had been able to insert into another declaration of principles, ten years earlier. This had been drafted under much less favourable circumstances and was designed for the common programme of the various socialist, half-socialist and quarter-socialist tendencies in Europe and America. Wherever the Gotha Programme failed to meet this minimum condition, Marx considers it to have fallen below the level already reached by the movement. Hence, even if it appeared to suit the state of the Party in Germany, it was bound to harm the future historical development of the movement.”

Yet, neither Marx’s ruthless critique nor his development of the Marxist theory of transition to communism was understood. It was ignored and the Gotha Program emerged virtually unchanged in a rising tide of opportunism. The ‘vulgar’ Marxist program that mistook exchange relations for production relations was to lead to the betrayal of 1914, was adopted. “Why retrogress”? Marx asked. Engels and Lenin provided the explanation later. The emergence of German imperialism could now afford to create a labor aristocracy bought off by rising living standards paid for by colonial super-profits. German Social Democracy was adapting to the formation of a labour aristocracy which voted for state reforms paid for by the super-exploitation of colonial workers and peasants. If the Gotha Program turned its back on the Communist Manifesto and founded German social-democracy as pre-Marxist ‘vulgar socialism’, was the Erfurt Program of 1891 any better?

Engels and Lenin critique the Centrist Erfurt Program of 1891

The Erfurt program in 1891 fails to break completely from the Gotha Program in its central aspects. It is a centrist program at best. Engels’s letter ‘On the Critique of the Social Democratic Draft Programme of 1891 (the Erfurt Programme)’ is a continuation of Marx and Engels critique of the Gotha Program. Engels was clearly prepared to continue the fight for the Communist program against the emerging opportunist German Social Democracy and its main theoretician, Karl Kautsky. He published for the first time Marx’s Critique of the Gotha Program alongside his own Introduction to Marx’s: The Civil War in France in 1891 to publicly champion the lessons of programmatic development since 1847, yet his Critique of the Erfurt program was not published by Kautsky until 1901! The substance of Engels critique, like that of Marx at Gotha, was ignored. The gulf between the Communist Manifesto and the reformist German SPD, behind the hollow Marxist phrases, was growing wider.

Engels main critique is of the “opportunism” of the political demands: "These are attempts to convince oneself and the party that “present-day society is developing towards socialism” without asking oneself whether it does not thereby just as necessarily outgrow the old social order and whether it will not have to burst this old shell by force, as a crab breaks its shell, and also whether in Germany, in addition, it will not have to fsmash the fetters of the still semi-absolutist, and moreover indescribably confused political order... In the long run such a policy can only lead one's own party astray. They push general, abstract political questions into the foreground, thereby concealing the immediate concrete questions, which at the moment of the first great events, the first political crisis, automatically pose themselves. What can result from this except that at the decisive moment the party suddenly proves helpless and that uncertainty and discord on the most decisive issues reign in it because these issues have never been discussed? ... This forgetting of the great, the principal considerations for the momentary interests of the day, this struggling and striving for the success of the moment regardless of later consequences, this sacrifice of the future of the movement for its present may be 'honestly' meant, but it is and remains opportunism, and 'honest' opportunism is perhaps the most dangerous of all..." [Our emphasis]

Kautsky evades the critique. He claims that Engels critique was of the first draft and not of his draft which was the one adopted. Yet a comparison of the two shows that Kautsky’s version does not reflect Engels critique of the political demands. Kautsky’s book Class Struggle, an extended commentary on his Erfurt draft, was published in 1892. It becomes the popular presentation of the Erfurt Program. Do Engels criticisms still hold of Kautsky’s book?

Kautsky’s Class Struggle expounds ‘orthodox’ Marxist ‘economics’ from surplus-value to crises of overproduction which create the conditions for the transition to socialism. But there are no dialectics, only an evolutionary schema of capitalist development. The proletarian side of the class struggle is rendered ‘objective’ as the subjective agency of the proletariat is suppressed and replaced by the petty bourgeois socialist intelligentsia. Capitalist ‘development’ is expressed by Vulgar Marxist intellectuals who lecture the workers on their level of development. The transition to socialism is managed by a socialist bureaucracy that reforms the transition of the capitalist state into the socialist state.

“From the recognition of this fact is born the aim which the Socialist Party has set before it: to call the working-class to conquer the political power to the end that, with its aid, they may change the state into a self-sufficing co-operative commonwealth.” [Our emphasis]

So for Kautsky “conquering political power means “change the state”. How? There is no armed insurrection or ‘smashing of the state’ but rather a relatively peaceful transition through the gradual take-over of the state or as Marx put it the “transfer the bureaucratic-military machine from one hand to another” (18th Brumaire). Therefore the political demands of Urfurt as presented by Kautsky for the transition to socialism fall far short of the Communist Manifesto and the critical development of the program in the period 1852- 1875 spanning the Commune to Gotha.

Lenin’s recognition that the Erfurt program was centrist did not come until after the great betrayal of 1914. From that point he went back searching for the material roots of the degeneration of German social-democracy. State and Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky were the result. In this process Lenin revisits Engel’s suppressed critique of Erfurt and in the process finds that Kautsky, the German leader who bases his authority on Erfurt, actually rejects all the decisive developments in the Marxist program since 1847. Referring to Kautsky, Lenin exclaims in marginal notes in his drafting of State and Revolution “This is as a complete wreck of Marxism...a step back from 1852-91 to 1847”! ['Marxism on the State: Preparatory Material for the book The State and Revolution'. Not online]

Why was Lenin taken in by Kautsky’s centrism for so long? The short answer is, first centrism itself, and second, Tsarism. It is the nature of centrism that it disguises its treachery in hollow phrases. While Engels chided the German Social-Democracy as ‘opportunist’ he thought this was an aberration probably resulting from self-censorship to avoid triggering Bismarck’s anti-socialist law. However, centrist opportunism is not exposed as a counter-revolutionary retreat from Marxism until it is tested in revolutionary conditions and is exposed by its treacherous actions. So the revolutionary phrases carefully qualified by vague euphemisms such as “conquering political power” in Kautsky’s program were not put to the revolutionary test of practice in Germany until 1914.

Second, developments in the SPD were not central to the class struggle that was developing in Tsarist Russia. The SPD was a legal party with millions of members, a large official apparatus, and many elected MPs in the Reichstag. Formally, it was standing on the Erfurt program and the “conquest of political power”. In Russia however, the pressing task for the Marxists was the smashing of the Tsarist state bringing with it a whole set of challenges to the program and to the form of revolutionary party needed to overcome these challenges. The necessary debates over theory and tactics became the focus of the factional disputes and machinations in the RSDWP. This is evident in the fact that the RSDWP leaders while in exile in Europe conducted disputes in their own papers and congresses almost independently from the 2nd International parties in their host countries.

Currently there is a debate around whether the RSDWP was a Marxist party in the mould of the SPD of Kautsky, the ‘mother’ party in the 2nd International, or a party of a ‘new type’ as a result of Lenin winning a majority in 1902. The SPD was a ‘mass’ party but it was also a ‘broad’ party of Marxists, centrists, and reformists where the Marxist faction was marginalised by the centrists and were unable to defend the Marxist program of the dictatorship of the proletariat against the opportunists. This question was glossed over since workers were experiencing rising living standards via parliamentary reforms and the program was watered down by the reformist wing of Bernstein under the cover of Kautsky’s centrist wing. So while the reformist wing was critiqued by the centrist Kautsky at the same time he opens the door to the retreat from ‘smashing the state’.

Lenin asks: "How, then, did Kautsky proceed in his most detailed refutation of Bernsteinism? He refrained from analyzing the utter distortion of Marxism by opportunism on this point. He cited the above-quoted passage from Engels’ preface to Marx’ s Civil War and said that according to Marx the working class cannot simply take over the ready-made state machinery, but that, generally speaking, it can take it over—and that was all. Kautsky did not say a word about the fact that Bernstein attributed to Marx the very opposite of Marx’ s real idea, that since 1852 Marx had formulated the task of the proletarian revolution as being to “smash” the state machine." (Lenin Chapter 6, State and Revolution)

In Russia the “task” of the RSDWP was not the working class “conquering political power” from the bourgeoisie, but that of leading all the oppressed masses in the overthrow of the Tsar. The RSDWP began as ‘broad’ party like the SPD but its Marxist faction (Bolsheviks) from 1902 dominated the opportunists (Mensheviks) and the conciliators (Centrists) in its militant defence and development of the Marxist program. The showdown between Marxist and opportunist factions came to the surface in Russia even before 1905 as theoretical differences on strategy and tactics had life or death practical consequences in combating the Tsarist autocracy.

Lenin and ‘What is to be Done?’

Unlike the SPD which could vote its representatives into Parliament, the Russian party faced a Tsarist autocracy. The immediate task was that of ‘political freedom’, that is the bourgeois revolution, in which the proletariat would be the leading class. Lenin’s conception of the party was not as a professional elite separated from the mass membership, but of both intellectuals and workers who took the Marxist program to the workers already organising against the Tsarist regime. The differences in the RSDWP didn’t arise over the program to overthrow of the Tsar but over the role of the proletariat in this revolution. For Lenin and the Bolshevik faction the proletariat must be independent of the bourgeoisie and lead all the oppressed classes. For the Mensheviks, like the centrists of the SPD including Kautsky, the proletariat was not capable of taking the place of the bourgeoisie in leading the bourgeois revolution alone.

Thus between 1902 and 1917, the main fight inside the RSDWP was between those who argued over whether that working class was ready or not to take the place of the bourgeoisie in overthrowing the Tsar. The Bolsheviks thought it was ready, the Mensheviks thought that the workers would have to ‘compromise’ with the bourgeoisie.

On the question of the nature of the vanguard party, this is determined by the Marxist program in which the proletariat is the only revolutionary class capable of fusing Marxist theory and practice as the agency of revolution. Specific national conditions are the immediate concrete workings of this historic and international class dialectic. The Tsarist regime oppressed not only workers but poor and middle peasants. It also oppressed elements of the bourgeoisie. Lenin argues that the working class will lead the revolution bringing behind it the poor and middle peasants. The rich peasants are becoming capitalist and they and the weak bourgeoisie cannot lead a revolution against the Tsar. Thus the proletariat will be ‘hegemonic’ in leading all the oppressed classes. For that to happen the Marxist party must include the vanguard of workers who have a ‘socialist consciousness’ and not those who are only ‘trade union’ conscious.

In What is to be Done (WITBD) Lenin famously says that this ‘socialist consciousness’ is brought from outside to the workers. Rather than an admission that the Marxist party is separate from the workers, the so-called ‘dictatorship of the Party’ criticised by Luxemburg and Trotsky, it’s the opposite. Both the workers movement and the Marxist intellectuals must ‘converge’ and ‘fuse’ for the revolution to happen.

That is why the Bolsheviks split organisationally from the Mensheviks in 1912, while the Marxists in the SDP failed to build a Bolshevik type faction until the KDP (Spartacists) in 1919. The party that would lead the overthrow of the Tsar and organise the socialist insurrection became a ‘mass’ Marxist party in which the members were in agreement with the Bolshevik program for Russia. Tragically, in Germany the Spartacists founded the KDP too late in 1919 but were ‘smashed’ by the SDP reformists and by Kautsky’s USDP who joined a popular front bourgeois government in the ‘peaceful transition to socialism’ that was neither peaceful nor a transition.

So in 1902 Lenin is already providing answers to the questions posed above: the RSDWP is not yet a vanguard party. Its leaders and members are Marxists but there are differences on how to overthrow the Tsar. After 1905 the party fragments into numerous weak factions but around 1909 the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks reform and their differences deepen over strategy and tactics. A split looms and comes to a head over whether the working class will lead the overthrow of the Tsar or do so in a political coalition with the bourgeoisie. Lenin mobilises to reorganise the RSDWP on a Marxist program of a worker-led revolution, against Mensheviks and others who want a cross class coalition. The program comes first and the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks split in 1912.

From this point on both factions organise and meet separately presenting a clear choice for Russian workers. They enter the period of rising struggles and prove to the masses which program is correct and which class will lead the revolution against the Tsar. This will happen first in 1914 when the Bolshevik faction becomes the core of the Zimmerwald Left and an embryonic new international. It will come to the ultimate test when the Bolsheviks convince Russian workers to make a revolution, and the Mensheviks side with the peasant petty bourgeoisie and the bourgeoisie to oppose the revolution. This is democratic centralism in practice and it was tested in practice, and in its absence, with positive and negative results in the Russian and German Revolutions.

Some neo-Kautskyites today who want to recruit Lenin to the ‘broad’ party fail to grasp that while the Bolsheviks and Mensheviks did not form separate parties in 1912, they split as factions over a fundamental principle of the Marxist program. The RSDWP that resulted contained two parties, except in name, the Bolsheviks standing on the principle of worker ‘hegemony’, the Mensheviks on ‘class conciliation’ (what is called today the popular front with the bourgeoisie) in the Russian revolution. Far from being a ‘broad’ party that tolerated all political differences, a split over this question was a matter of life and death. The failure to form the Bolsheviks as a separate political organisation would have wrecked its ability to implement democratic centralism and prevented it from rapidly developing its program and winning the masses support in the Soviets for a workers’ revolution.

Even so, in the Bolshevik faction in April 1917 all the leadership apart from Lenin were conciliating with the Provisional Government – that is, proposing a popular front with the bourgeoisie! The situation was rescued by Lenin because he could appeal to the mass base of the Bolsheviks won to the faction/party since 1912 on a Marxist program, and convince them of the correct strategy and tactics. Had the RSDWP not split and stayed as a ‘broad’ party of Marxists and class collaborationists like Kautsky’s SPD the outcome would have been a defeat for the Russian revolution at the hands of Kerensky and Kornilov! The Russian and German revolutions are the ultimate testimony to this fact.

Bolshevism and the Russian and German Revolutions

In April 1917 Lenin proved that the RSDWP were really two long term factions in name only and in reality two separate parties. Moreover he proved that the Bolshevik ‘faction’ was not free of would-be Mensheviks in the leadership ready to ‘conciliate’ with the bourgeoisie. It was necessary to go to the mass membership of the RSDWP. He read his April Theses to the Bolsheviks and then to both Bolsheviks and Mensheviks together. Lenin goes outside the Party Leadership and addressed the Petrograd branch of the party directly. He won them to the socialist insurrection. (Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution, (HRR) Chap 15).

Again in October Lenin is in a minority of one in the Central Committee. He demands an insurrection and the Central Committee burns his letter. Accusing the Central Committee of ‘Fabianism’ he then goes to the Petrograd soviet and the Regional Conference of Northern soviets and speaking on his own authority demands “an immediate move on Petrograd”. (Trotsky, HRR, Chap 24.). Then when the Central Committee finally agrees to the insurrection, Zinoviev and Kamenev disclose these plans in Pravda, the Menshevik newspaper. Lenin calls for their expulsion but is defeated on the Central Committee. This was how the Bolsheviks under Lenin’s leadership and organised as a de-fact0 mass vanguard party were able to not only survive a revolutionary crisis, but win the leadership of the workers and peasants, defeat the counter-revolution and make the first socialist revolution in history. Not so in Germany.

Not till August 4, 1914 was the theoretical bankruptcy of 2nd International put to the test and exposed as a ‘stinking corpse’ (Luxemburg cited in Lenin). The centrists around Kautsky and the Zimmerwald Left revolutionaries around Luxemburg and Liebknecht split to form the united SDP (USPD) but the left Spartakustbund faction in the USPD failed to break away to found an independent Bolshevik-type party until December 1918. Only in 1917 did the paths of the Russian and German revolutions converge in a Marxist leadership that understood the revolutions must unite to succeed. But the German ‘old guard’ around Luxemburg lacked the experience in organising a mass base. Their reliance of on ‘spontaneity’ against Lenin’s ‘centralism’ meant that when the soldiers and sailors rose up against the Junker regime there was no Bolshevik-type democratic centralist party at its head to ‘smash the state’. Like Lenin, Luxemburg facing a revolutionary crisis in Germany, returned to Marx and Engel’s to draw the lessons about the ‘smashing of the state and to refound the Communist program:

"...Down to the collapse of August 4, 1914, the German Social Democracy took its stand upon the Erfurt programme, and by this programme the so-called immediate minimal aims were placed in the foreground, whilst socialism was no more than a distant guiding star. Far more important, however, than what is written in a programme is the way in which that programme is interpreted in action. From this point of view, great importance must be attached to one of the historical documents of the German labour movement: the Preface written by Fredrick Engels for the 1895 re-issue of Marx’s Class Struggles in France. It is not merely upon historical grounds that I now reopen this question. The matter is one of extreme actuality. It has become our urgent duty today to replace our programme upon the foundation laid by Marx and Engels in 1848. In view of the changes effected since then by the historical process of development, it is incumbent upon us to undertake a deliberate revision of the views that guided the German Social Democracy down to the collapse of August 4th. Upon such a revision we are officially engaged today...." (On the Spartacus Program [our emphasis]

Too late! The delay of the revolutionary Marxists in splitting from the USPD was fatal. It meant that they did not have time to build a Marxist vanguard and win a mass base before the revolutionary crisis came to a head. By the time the Spartacists founded the KPD in 1919, the SPD and USDP were collaborating in a Bourgeois government led by the SPD leader, Ebert. The revolution, its main social democrat leaders were murdered and its armed workers’ militia ‘smashed’ by the Freikorps.

So the problem of the party is not that Lenin abandoned the ‘broad’ party for an elitist party, but that without a revolutionary program tested in the struggle the vanguard party is sucked back into opportunism and conciliation with the bourgeoisie. The problem is not therefore historic Bolshevik/Leninism but its absence. Russia and Germany are the test cases. The Bolsheviks won the masses in Russia because they split from the Mensheviks, but in Germany where they failed to split from the Kautskyites until too late, the revolution was defeated.

For both Marx and Lenin the vanguard party is the party of the Marxist workers not the party of non-Marxist workers. This was true even when the vanguard was no more than one; Marx on Gotha, Lenin on the April Theses. But at the same time the Marxist vanguard is obliged to fight to win the non-Marxists to the vanguard. But to do this the backsliding compromisers, opportunists, centrists, Mensheviks etc have to be defeated. This is what the Russian revolution proves. Like Marx confronting the retreat into Lassalleanism at Gotha, Lenin also finds himself alone in April 1917 carrying the banner of the Marxist vanguard.

As the crisis of war and revolution unfolded Lenin drew further conclusions. After 1914 he writes a series of articles and pamphlets and accuses Kautsky of reneging on the 1912 Basle Manifesto on war. (See Preface to ...Renegade Kautsky). In his Imperialism written in 1915 Lenin shows that Kautsky’s opportunism explains his theory of 'ultra-imperialism'. During the 1917 July Days when he is in hiding, he drafts the State and Revolution. He now shows that Kautsky abandoned the theory of 'smashing the state' in 1871. He “wrecks Marxism” and goes back to 1847.

Then in 1918 Kautsky’s condemnation of the Bolshevik revolution in his pamphlet ‘The Dictatorship of the Proletariat’ provokes Lenin’s brilliant The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky, in which he sums up Kautsky in the phrase “How Kautsky turned Marx into a Common Liberal” - by reducing the ‘Dictatorship of the Proletariat’ in the Paris Commune to ‘bourgeois (i.e. pure) democracy’ i.e. and electoral majority! The final nail in Kautsky's coffin is that his centrism is exposed as the key to the defeat of the German Revolution. It is Kautsky and the USPD that delays the founding of the German KDP until it is too late, then takes responsibility for the state repression of the Communists, defeats the revolution and thus prevents the Russian revolution from spreading to the world. Yet this is the Kautsky of the Erfurt program that the neo-Kautskyists like the CPGB wants to return to today!

The Party embodies the Program

For Marx the proletarian party is the Marxist party. The Gotha Program retreated from Marx’s method and his critique of Capitalism to Lassalle’s pre-Marxist exchange theory. The Erfurt Program restored the Marxist critique of Capital formally by returning to the production of surplus-value, but didn’t escape the Gotha Program in its reformist approach to the capitalist state. In the SPD the ‘broad’ party submerged the revolutionaries in a rising tide of opportunism. Engels critique was ignored as was Marx’s at Gotha. Kautsky vulgarised Marx, ignoring the laws of capitalist development, the crises of overproduction and the growing competition between the imperialist powers. The approaching imperialist war was something that could be stopped by a SPD majority in the Reichstag acting with ‘legality’! This had tragic practical consequences for millions of workers the world over 1000 times that of the Paris Commune. And this time it was done in the name of Marxism!

Today against the program and party of Kautsky, we need program and party of Marx. From Marx and Engels in 1847 to Lenin in 1924 the Marxist mass party was always based on workers who understood that to escape inevitable capitalist crises and imperialist wars they had to smash the bourgeois state and impose the Dictatorship of the Proletariat. If it fell short of that when its leadership adapted to imperialist super-profits and the labor aristocracy then it’s ‘party’ would end up being used by the bourgeoisie to destroy the revolution. Such a retreat into vulgar socialism was inevitable unless a Marxist vanguard was built capable of drawing the important lessons of organising and arming the proletariat to smash the state and replace the crisis and war ridden capitalist system with socialism. The German Revolution was defeated because it lacked a revolutionary program and party. Marx and Engels fought to test and develop the communist program all of their lives against non-Marxist and then revisionist Marxist currents. Lenin and Trotsky took on the responsibility of defending and developing that program after Engel’s death. Lenin in particular took the lead in the fight against opportunism in the period before WW1. That is why the Bolsheviks under Lenin and later Trotsky, and not the German SPD under Kautsky and Co. was the only Marxist party to defeat reformism and centrism and make a revolution.

Let Lenin have the last word on Kautsky: "Kautsky takes from Marxism what is acceptable to the liberals, to the bourgeoisie (the criticism of the Middle Ages, and the progressive historical role of capitalism in general and of capitalist democracy in particular), and discards, passes over in silence, glosses over all that in Marxism which is unacceptable to the bourgeoisie (the revolutionary violence of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie for the latter’s destruction). That; is why Kautsky, by virtue of his objective position and irrespective of what his subjective convictions may be, inevitably proves to be a lackey of the bourgeoisie." (The Proletarian Revolution and the Renegade Kautsky)

Who is the renegade, Lenin or Kautsky? The renegades of Marxism are those who abandon the program of the Dictatorship of the Proletariat. Most of what passes for the revolutionary left today are longstanding centrists known for their revolutionary phrases and reformist practice! They emerged out of WW2 with Stalinism intact and a ‘2nd world’ opposed to the imperialist 1st world. The Trotskyist Fourth International lacked roots in the working class and its efforts at keeping the Leninist/Trotskyist program alive founded on the long boom and reformism of Stalinist and Social democratic parties. Most revised Marx’s Capital into some form of exchange theory and drew the practical consequence of a minimal program of ‘equal rights’ via ‘state aid’. Thus most became adjuncts of social democracy, Stalinism, or 3rd World freedom fighters.

The restoration of capitalism in the Soviet Union and other former ‘degenerate workers states’ has deprived them of their defence of workers property. Some like the Spartacist family insist that hope lives on in China. Others liquidate into ‘anti-capitalist’ formations which are ‘broad parties’ including reformists and revolutionaries. Those who still pay lip service to Leninism (and/or Trotskyism), and those who are anti-Leninist, all end up on the same centrist swamp. They are a new batch of Mensheviks with minimum programs and petty bourgeois leaderships that they substitute for the Marxist vanguard. For example, the Spartacists substitute the Maoist bureaucracy in China; the Morenoists substitute the trade union bureaucracy; the Cliffites, the student intellectuals; and the Woodites, populist demagogues like Chavez–all trapping the proletariat in popular fronts with the bourgeoisie.

Yet these petty bourgeois pretenders cannot suppress the class contradictions as they re-emerge in current and future crises, wars, revolutions and counter-revolutions. Revolutionaries have to act as a vanguard of hundreds and thousands to expose the centrists by building militant internationalist united fronts everywhere with demands that advance the workers cause and force the centrists to declare themselves as class traitors. In the process the embryonic vanguard will like Lenin’s Bolsheviks, converge, and fuse with the millions of rising militants to build a new world party of revolution. A Marxist revolutionary international will be reborn as the terminal crisis of capitalism exposes the new batch of Mensheviks as class traitors. Arising out of the ashes of historic betrayals and defeats of the 20th century marked by the first Bolshevik revolution will be the revolutionary Marxists based on the Leninist/Trotskyist program of 1938 who go into the working class to build the Marxist vanguard to make the second Bolshevik Revolution in the 21st century.

“The victory of communism is inevitable, Communism will triumph!” Lenin, 'Greetings to the Italian, French and German Communists’. October 1919

No comments:

Post a Comment